hi,

Mark Zuckerberg said that 2023 will be the year of efficiency, so far he seems to be right. You have probably also witnessed accelerated cost-cutting activities in your own organisations. The question, "Do we have too many managers?" is usually asked at some point in those cost conversations, and 'Span of Control' is then the indicator that organisations usually turn to. And the simplistic approach to Span of Control is “the more the better”.

We need to be careful about Span of Control. I want to lay out a few reminders here that might hopefully help your thinking around this issue. The arguments and this article is on purpose simplistic rather than going deeper into the organisation design principles at length.

Span of control refers to the number of employees that a manager oversees, or simply put number of direct reports per supervisor. Span of Control can be wide or narrow. Wide means a large number of direct reports mostly 12 or more; narrow, a small number, 4-6.

In this issue, I will argue that wide spans of control hurt your business more than it saves cost. To understand why, we need to differentiate two terms: Span of Control vs Organisation Layers.

Span of Control vs Organisation Layers:

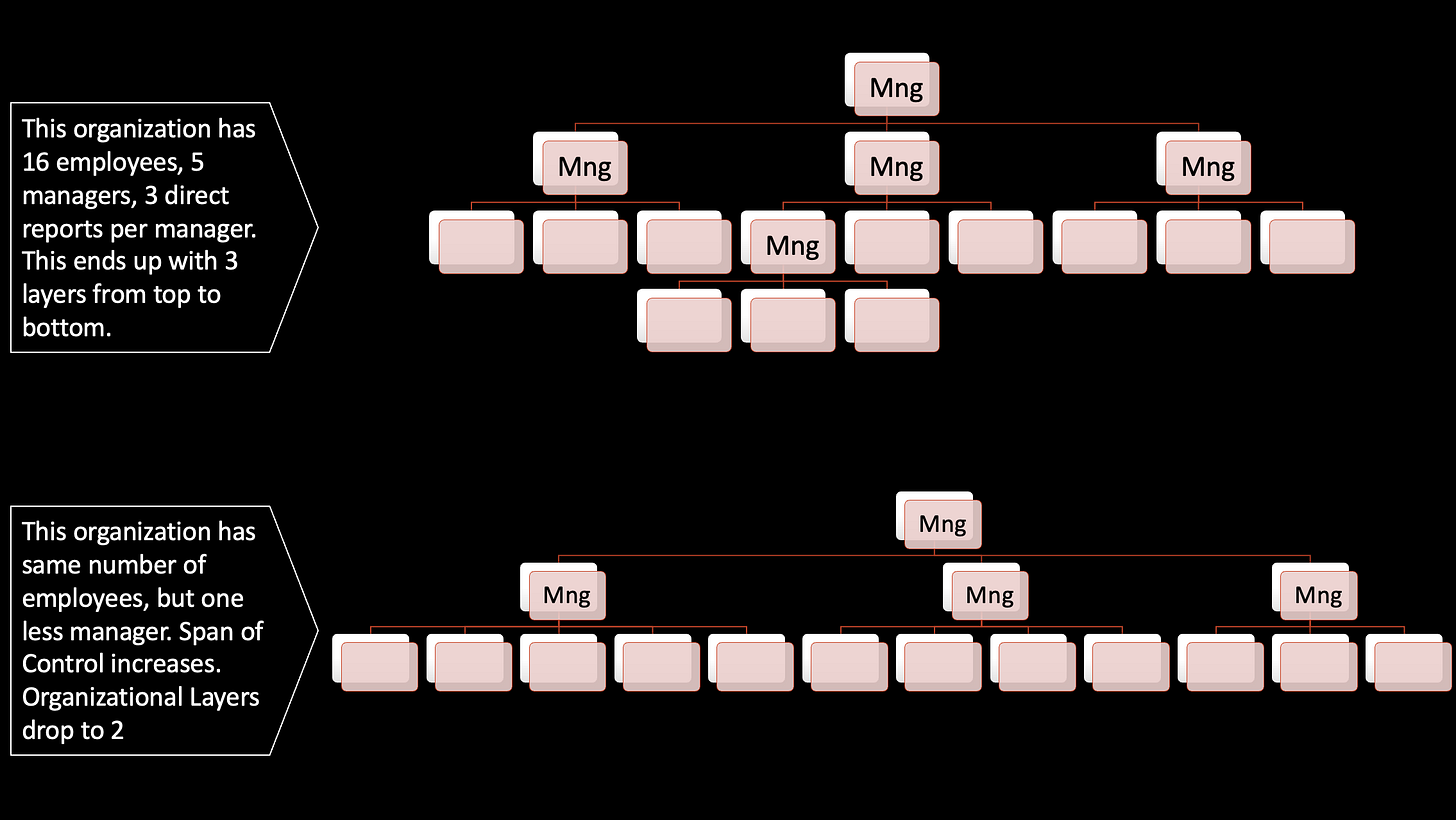

Organisation Layers indicate how many layers exist from the top manager to the lowest level. The top manager is usually one level below the CEO because organisations want to examine each unit's layer independently. In a large unit of a few thousand people and more, a typical number of layers is 7 or 8, anything more would be unusual.

Organisation Layer is crucial for having a lean and agile organisation. The more organisation layers a company has, the slower the information flow will be and the slower the decision making will take place. Execution also becomes faster when the organisation layers are kept to a minimum.

Span of control and organisation layers are connected. If your average Span of Control is narrow (like 3 or 4) then it is likely you will have extra layers in the organisation. A simple illustration is below.

There are two arguments to maximise the Span of Control:

To keep the organisation lean and the organisation layers to a minimum (as seen above).

To avoid unnecessary cost that comes with managerial compensation and benefits.

I will now present the balancing argument that a wide Span of Control can also lead to significant loss of productivity and motivation.

Here are some simple principles, based on my years of experience as a consultant at Hay Group and previous companies:

The optimal median Span of Control for organisations is between 8 and 10. I am assuming the organisation has a mix of units of production, sales, marketing, support functions, R&D etc.

CEO and senior management positions work best with around 7 direct reports, not including functions that often reported in a dotted manner to the leader (eg: Finance, HR, Legal).

Highly expertise areas should have a manager for each 6-10 experts. Repetitive, transactional work like call-centre agents can be in units of 12-15.

I prefer to intervene with any team that has larger than 15 employees reporting to a manager. And I usually demand a business rationale for any management position with less than 6 direct reports. Anything between 5 and 16 are within the range, and needs no intervention.

You can also see the practical applications like the famous Amazon “two pizza team” concept and Spotify’s “Pods”, smaller, faster teams.

All numbers above are highly dependent on leader capability, organisation culture, nature of work, geographic dispersion, supporting infrastructure, etc. I don’t mean to mechanise sensitive decisions like reporting lines, I merely want to set a framework for everyone to deduct their own from.

Intervening with crowded units:

One of the challenges I have faced is to persuade executives to divide crowded units. In my past, most executives I came across took large Span of Control numbers as a sign of efficiency. “A manager with 22 direct reports? Well done!”. It is difficult to come on that note and say “we need to divide this unit and add a manager”.

Here are some frame arguments:

I see the main duties of leaders as problem solving and talent enablement. We can argue about adding more to the list, but whatever we add will require cognitive capacity (especially for tough problems) and quality time with their employees.

The amount of administrative work per employee has significantly increased for leaders. As we have downsized personal assistants, we have put everything on the shoulders of managers as “self service tasks” without formulating good interfaces. The tasks like basic vacation approval, entry card ordering, sick leave, phone usage, mouse request, and many others take a long time. Multiply those tasks by 16 or even 20, we drown leaders. They also become frustrated during the process.

The value-added HR processes are time consuming: performance reviews, career planning sessions, roundtables, feedback check-ins, salary increase conversations, grade conversations, development needs. They pile up when you need to do all those for 20 employees. Unfortunately in most cases, leaders either skip those tasks or do them very poorly. This heavily cripples the talent enablement piece I referred to earlier. The result is unhappy employees because they haven’t received the right career coaching and feedback, and overloaded leaders who do things as part of mandatory processes rather than investing time to genuinely develop their people.

Working together with the team members is a central role of the manager; coach them when they hit a wall, provide them air-cover when they present to management. These are valuable on the job coaching activities that create trust and develop the employees. They require time and for the leader to know the work agenda of their subordinates. With a direct report number of 18, a leader will not be able to do this valuable coaching.

In large units, the leader sometimes then creates sub-groups, privileged employees that have more access to the leader and decision making. Some leaders will call them the “inner circle” or the “core team”. A concept that hurts the inclusion and belonging aspects. Feeling of inclusion is not only about being invited to meetings, it is mainly about being included in the decision-making process and information flow. With a large team, it is challenging to create an inclusive context.

With so much to handle, and additional behaviours we expect from the leader like empathy, disruptive thinking, collaboration, innovation,.. we are drowning our leaders when we allocate 16-20 subordinates to them. In turn, the leader will not have the time for focused thinking, or internal networking for collaboration. The challenging and exciting sides of the role become buried under administrative tasks for 20 people.

All five bullets above are substantial conversation in themselves, but I hope they give an idea of the dangers of having a wide Span of Control. Unfortunately, it is hard to observe the negative aspects of those five items above in daily work. They harm the organisation in quiet ways and over the mid/long-term.

Good to test a few things in your organisations:

Attrition rates in crowded units vs less crowded ones.

Leadership scores of managers with wide Span of Control.

Engagement scores of managers with crowded teams, and the engagement scores of the subordinates compared to teams with 7-8 employees.

Similar indicators will give you good ammunition for your arguments.

An alternative solution frame for teams with wide Span of Control:

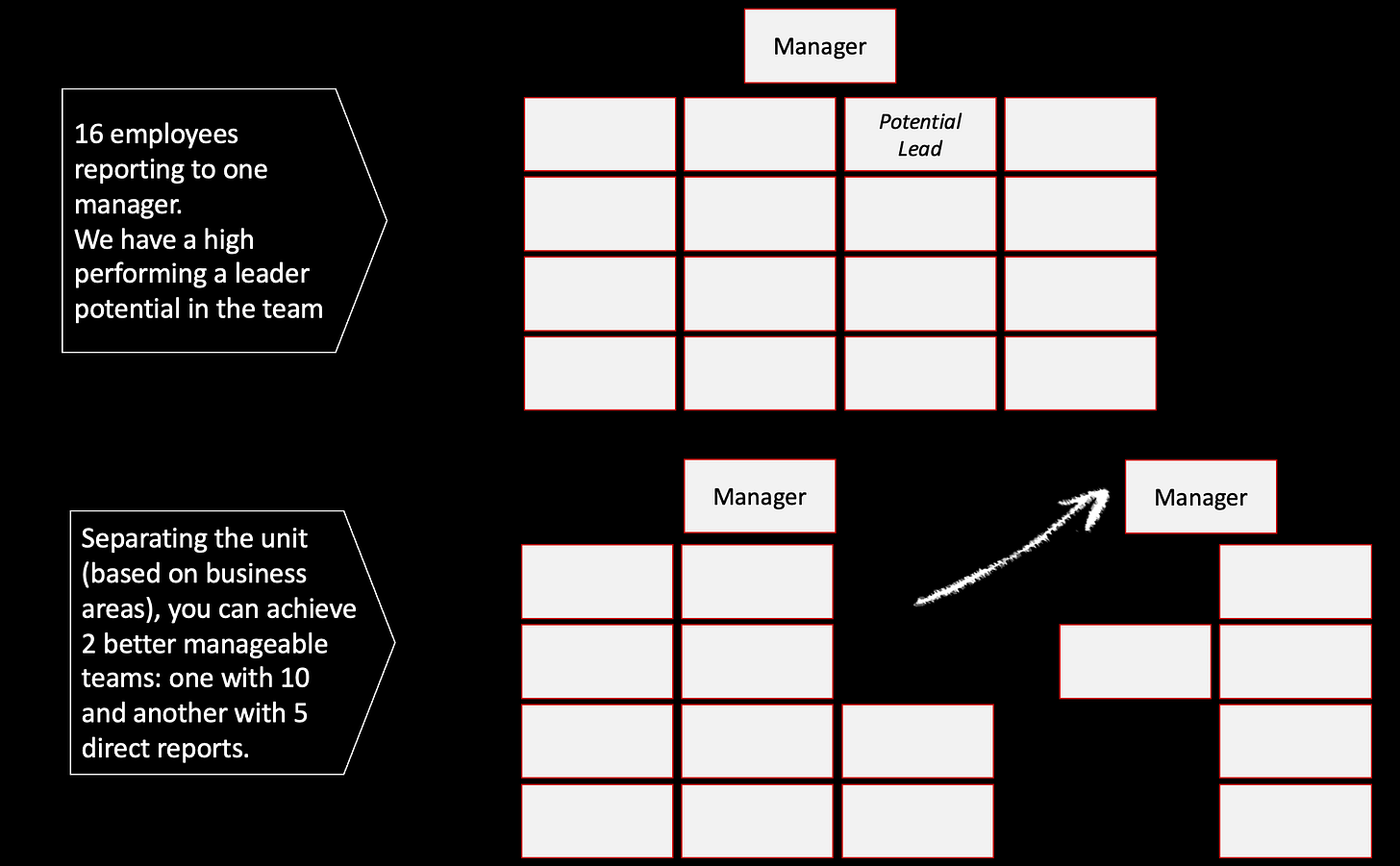

Promote someone within the team as the second manager, when we divide a unit. We reestablish the “manager position” as half-doer / half-leader, so that the headcount should not be replaced. That avoids the extra cost of one extra person. This also redefines what you expect from managers, you want leaders that are more involved rather than task coordinators. This move will increase the number of direct reports of the manager above (the grandparent), check if that is manageable for the incumbent.

Promote members of the team who have capacity for progression; you already prepare for the future leadership. In that way, with a smaller team you will have that person actively develop for the future bigger roles. Sends a strong signal to rest of the team as well.

Below you see an illustration of this potential solution with a unit of 16. For larger units you can think of dividing the unit into 3 pieces as well.

There is a risk of demotivating the initial manager, as their scope will decrease. Something to remedy before you make those changes. I usually prefer those changes when we need to change the leader.

Side Note: The difference in compensation between managers and highly expert employees should not be too wide. Moreover, organisations should be ready to compensate experts higher than their managers if the output of the expertise work is more impactful. One of the sad effects of giving managers company cars, power and influence is that good technical experts tend to aspire to be leaders.

To watch out: Clustering Different Domains

Organisations sometimes cluster sub domains together to get bigger units, wider span of control. You see related domains getting clustered under a one leader usually a senior leader managing one of the domains. An example would be a sales executives managing 7 Sales district managers, and you add 4 marketing product managers to “increase efficiency” to that unit. You have now 11 direct reports but a sales leader leading marketing, probably lacking the core expertise in that area and spending more focus on sales. It is good to watch out for those efficiency moves that will hurt the organisation in the long run.

Conclusion

Span of Control is an important but also a very contextual indicator. There is a knee-jerk reaction from companies and consultants to increase the Span of Control and decrease the number of managers in any cost conversation. I suggest that organisations approach this with a bit more caution, be aware of the risks to push the Span of Control too much. Savings on paper like “we have decreased the number of managers by 5%” might have significantly negative second order effects on productivity and work output.

On the other end of the spectrum, having an average Span of Control of 4-6 also means that you need to look at merging some of those units, where it makes sense.

Good to keep in mind that the closely correlated indicator “Organisation Layers” should be the main focus if organisations suffer from slow decision making and lack of execution.

As with all issues of IF INTERESTED, my aim is to start a conversation rather than give conclusions. The topic of Span of Control is widely known, and some of the remarks above are more reminders than novel solutions.

If interested.

burak

Some extra notes

How to calculate Span of Control:

Usually I prefer to use median rather than average with every HR metric. Average is susceptible to extreme values. So, also here I prefer median Span of Control number.

Span of Control should be calculated by the median (or average) or every manager’s direct report number. Some companies use a different method of dividing the total number of employees to total number of managers, which is slightly misleading.

History of Span of Control:

Span of Control has been a topic of discussion going back to the ancient Egyptians, but lately Napoleon Bonaparte, defined the SOC concept as “not having more than a span of five distinct bodies” (Altham, 1914). A major contributor to the topic is a management consultant from France named Graicunas, who in the 1930s identified Span of Control dynamics through relationships between supervisor and employee, and between team members, and decided 4 should be the ideal number of subordinates.

Further reading:

Here is a McKinsey article. It has some good nuggets, but focuses on cost saving element, as expected.